Superconductive Systems

Make the easy choice lead to a good outcome

CC0 (Public Domain Dedication): This work is dedicated to the public domain under Creative Commons CC0. You may copy, modify, distribute, sell, or use it for any purpose without permission or attribution.

Stop fighting the river. Change the banks.

Most managers spend their careers fighting gravity: persuading stubborn coworkers, patching broken processes, or trying to “motivate” people who are already exhausted. They treat this as a communication or character problem. It isn’t.

The real issue is that there will always be exhausted people, and exhausted people shortcut to the easiest thing in the moment. If that behavior produces bad outcomes, that’s a systemic failure, not an individual failure.

Managers often try to motivate people out of exhaustion, but that is a losing—and exhausting—battle. Willpower, attention, and energy are finite resources. Systems that depend on them eventually fail.

A more effective approach is to design the system so that when people take the easiest path in the moment, that path still leads to a productive outcome. Then ensure this remains true across all major behavioral modes people may exhibit.

A Superconductive System is one in which the path of least resistance for all major behavioral modes leads to productive outcomes—even when people are stressed or tired, and even when the manager isn’t present.

This minimizes energy loss, creating highly efficient and resilient systems.

It means good outcomes still emerge:

when workers are exhausted,

when managers are unaware of their team’s current mode,

and even when managers aren’t present at all.

Crucially, it also means the manager no longer has to spend constant effort persuading, reminding, or policing behavior.

Diagnostic Lens

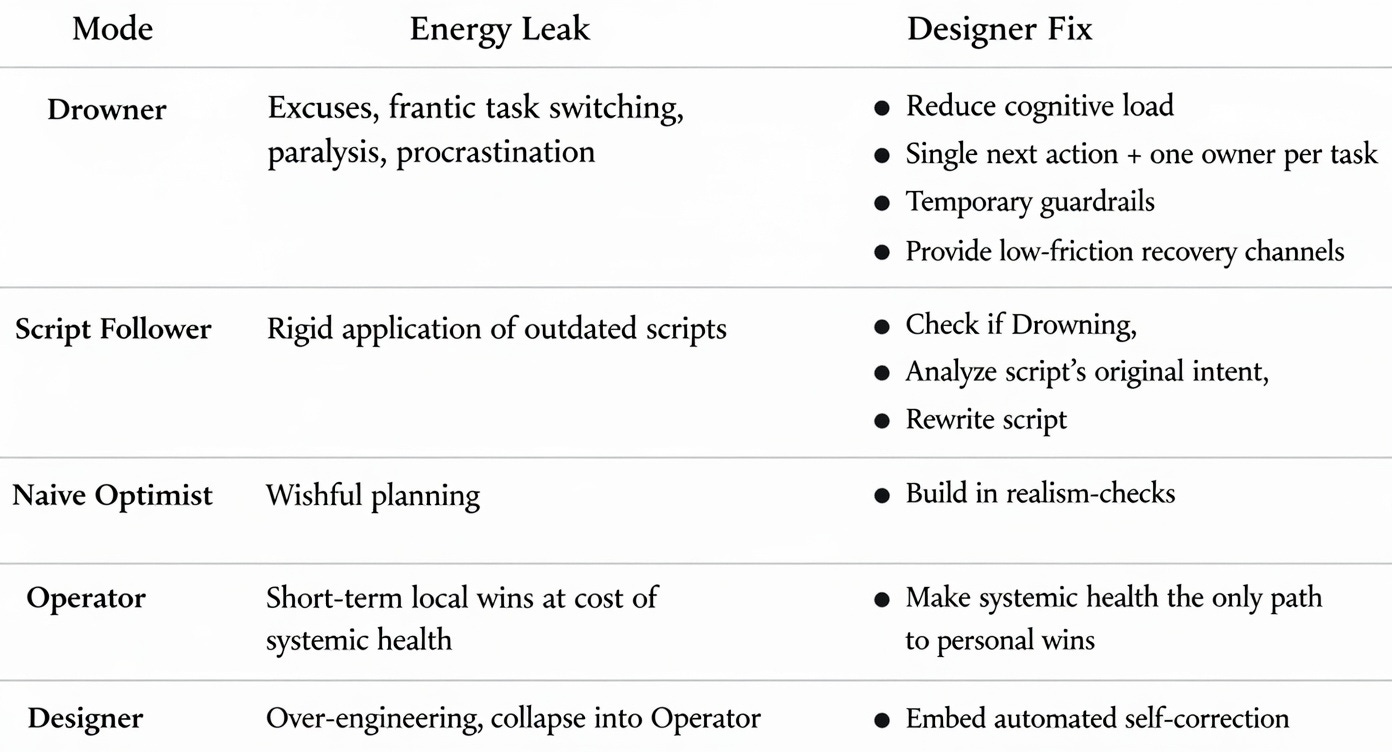

In almost any domain, if you see that someone (or yourself) is underperforming and you diagnose their current mode, then you know how to intervene:

These are behavioral modes, not fixed identities. People regress under stress, including Designers. No one is a Designer 100% of the time, and everyone experiences Drowner moments. A Superconductive System supports people through those moments.

Not everyone fits cleanly into one of these modes. Many capable Product Owners, for example, combine realistic assessment with solid long-term system thinking, yet they work within the system rather than redesigning the river’s banks.

Context dictates the mode: A Product Owner might be a Designer regarding their team’s Jira workflow, an Operator regarding the department budget, and a Script Follower regarding HR compliance. People inhabit different modes depending on which “river” they are swimming in at the moment.

The Tragedy of the Optimist vs. the Operator

The Naive Optimist (e.g., Ned Stark) is competent but fails because they assume that just naively moving forward will work out, and because they assume everyone else is competent and well-meaning and on the same page. This cost Ned Stark his head.

The Operator (e.g., Tywin Lannister) understands reality but succeeds by extracting value. In the long term, or when the Operator leaves, the system often collapses. These people may be the most effective ones in the entire company, and also the most dangerous ones to its long-term health.

Meanwhile: the Designer creates systems that keep working even if they leave and someone mediocre replaces them—or if they have a horrible month and briefly collapse into Operator.

The Designer doesn’t achieve results by hollowing out the system. They achieve them by making the system itself more resilient over time. This is the antidote to today’s culture of hollowing out the system for quick wins.

The Designer doesn’t manipulate people. The Designer manipulates gravity.

Implementing A Superconductive System To Support Drowners

For example, the Designer can install these banks:

Single-Point Accountability: Each sub-task has one clear owner. No hiding behind shared responsibility.

Dual-Layer Reporting: Anonymous channels for reporting dysfunction are read by at least two people, ensuring that a single dysfunctional manager cannot intercept the feedback.

Proper system maintenance: Employees can visit a company psychologist (or external counselor) who has the authority to mandate two days of “recovery time” (not deducted from vacation) without disclosing the reason to the manager.

In this system, when a person enters Drowner mode, their behavior shifts—even without manager intervention. Procrastination is no longer the easy path—they don’t want to explain a stagnant task in a daily stand-up.

Instead, the new path of least resistance leads to productive or restorative outcomes:

Direct Action: They push through the task because the clarity of ownership makes starting easier than explaining a delay.

Systemic Feedback: They use the anonymous channel to report the stressor, giving the Designer data to fix the system.

Restoration: They use the “Proper system maintenance” psychologist. This stops an employee from unexpectedly falling ill for months, which is far more expensive than having an employee take two days off. From the Designer’s perspective, it’s better to put a leaky pipe in maintenance for two days rather than have it leak for weeks and then suddenly break for months.

By constructing the system this way, the Drowner’s behavior leads to good outcomes even if the manager is unaware they are struggling.

The system runs automatically. It doesn’t require managerial effort and it doesn’t decay when the manager leaves the room.

Implementing this for all major behavioral modes makes the system Superconductive.

System Judo: The “Slow vs Fast Tasks” Case Study

Automated tasks are happening in a slow and fragile way. Leadership wants those automated tasks to be converted to faster, more reliable tasks. However, making new slow tasks is quicker in the short term, and converting tasks to the fast way takes time. Hence progress has stalled for more than a year.

Everyone agrees on the goal—but nothing changes.

Why the Obvious Approaches Fail

The Naive Optimist approach: “Let’s explain why this matters and trust people to do the right thing.” Result: People are busy, afraid of change, or protecting their own timelines.

The Operator approach: “We’ll track metrics and penalize non-compliance.” Result: People exploit loopholes, morale drops, and resentment builds.

The Designer Move: System Judo. Instead of arguing, persuading, or policing, the system’s gravity is altered by updating the Definition of Done:

The Boy Scout Rule: “Leave it better than you found it.” While working on a topic, spend a reasonable amount of time converting related slow tasks to fast tasks. To ensure this happens even when people are rushed, an automated process disallows adding new slow tasks unless an existing one is converted to a fast task.

If a slow task fails, don’t waste time fixing it when it will later be converted. Instead, either convert it to a fast task (and pass peer review) or document why it must remain slow (also reviewed).

Two automatically calculated metrics are added to the dashboard: “Avoidable Slow Task Tax” (hours lost per week to avoidable slow tasks) and “Unavoidable Slow Task Tax” (from tasks that cannot be converted). This turns invisible friction into a visible cost. The Designer labels the reality: “The reason we don’t have time is because we’re paying a high Avoidable Slow Task Tax. We have to spend some time in the short term to reduce our Tax burden.”

After a period of time, anonymous feedback and pain points about the rules and processes are actively gathered from all participants, surfaced without attribution, and incorporated into iterative refinements.

Why This Works

The Drowner:

Their path of least resistance has changed from “don’t convert tasks” to “convert tasks because that’s less stressful than documenting why they can’t and passing peer review.”

They take comfort in the fact that converting tasks will eventually reduce how much time they have to spend on maintaining fragile slow tasks.

They take comfort in the fact that if they spend short-term time on lowering the Tax burden, management can’t blame them for that without sounding foolish.

The Script Follower sees this as a legitimate rewriting of the script to promote excellence. They will faithfully follow the new, better script.

The Naive Optimist gets confronted with the reality check of the Avoidable Slow Task Tax and hence can make better decisions.

An Operator who is a worker has their path of least resistance changed from falsely saying “I can’t convert this” to converting the task, because they don’t want to publicly document why they can’t and submit that to peer review.

An Operator who is a Product Owner gets nudged into the rational direction of lowering the Avoidable Slow Task Tax. They can’t refuse to lower the Tax burden without looking foolish.

In the medium term, this System Judo move is good for literally everyone. Everyone benefits when the Avoidable Slow Task Tax burden is lowered.

A Naive Optimist or Operator would likely fail to persuade sufficient people to convert tasks. However the Designer likely succeeds thanks to this very efficient Superconductive System.

This system runs automatically, even when the manager isn’t in the room.

And the manager stops having to spend energy on monitoring people who aren’t converting tasks and trying to persuade them to do that.

All this has been accomplished fully transparently and ethically.

After an adjustment period, it’s likely that everyone feels good about this new way of working. Anyone who has a legitimate complaint can give anonymous feedback.

This same approach applies to a wide variety of other fields.

Tools Of The Designer

The Designer looks at bad outcomes in the current system.

The Designer sees that there is too much passive behavior. They diagnose the modes: Drowners are too exhausted to care, while Script Followers are waiting for permission.

Having already installed banks for the Drowners, the Designer now rewrites the script: ‘Once per quarter, everyone must submit an idea for improvement, or upvote an existing idea.’ Management publicly responds to the top two ideas.

The Designer makes sure that even if he’s not in the room, even if everyone is tired, the path of least resistance for people in all modes leads to good outcomes. Only then is a system Superconductive.

The Designer stress-tests this by asking: “What is the most selfish or lazy path through this current system, and how do I make that path lead to the goal?”

A primary Designer tool is having good defaults and Accurate Labeling. By naming a process accurately, they shift the gravity of how people interact with it. For example:

They name a meeting “Blocker Removal” instead of “status update”. This shifts the default behavior towards active problem-solving.

They allow psychologists to give employees time off without disclosing the reason to the manager, and call that “Proper system maintenance.” That accurate label turns an unthinkable idea into something that’s hard to argue against.

The Designer also reduces everyone’s mental clutter by making sure people aren’t distracted by noise or useless information, and that they have time to engage in deep thinking. The Designer deletes useless metrics that just draw attention away from what does matter.

At the same time, adding a bit of friction can help too. For example, merging code after 5 p.m., on Friday afternoons, or just before a major release adds a 5-minute enforced wait. This is a “speed bump” that triggers higher-level thinking.

The Designer builds in cheap resilience. They schedule monthly 15-minute walks named ‘Proactive Problem Identification (PPI) walks’ with critical people, so that the river flows in the direction of having the important conversation.

The Designer:

Makes the easiest thing in the moment lead to a good outcome

Makes the wrong thing visible, costly, and self-correcting

Minimizes enforcement

Ensures systemic health is the only viable path to personal success

Realize that they are in the water too, that they too are subject to biases and blind spots. Hence they design self-correcting systems that surface failures early and cheaply, including their own (as described in Appendix B).

Realizes that the more banks they add to the river, the more complex the system becomes, and the less legitimate it may feel to the people inside it. Banks added solely to handle edge cases are often net-negative.

If one of your policies would fail public defense to the people it affects, yet they have no way to remove it, then you are not a Designer. You are an Operator.

Designers must keep Goodhart’s law in mind: when a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.

A Designer Mode Failure Case Study

A team introduced a peer-feedback system designed to surface hidden work and reward collaboration. The incentives were clear. The values explicit. The metrics looked clean.

What the Designer missed: people optimized for visibility, not contribution.

Work fragmented. Performative updates increased. Quiet, deep work disappeared.

This exemplifies how visibility incentives can crowd out real contribution.

The Designer publicly admitted the error, dismantled part of the system, and absorbed the credibility loss.

This is what “watching the watcher” looks like: owning failure visibly, revising incentives openly, and accepting personal cost when the design harms meaning.

A Designer system does not avoid mistakes.

It makes them expensive for the Designer, not the people trapped inside.

If automated pruning of bad policies had existed, as appendix B describes, then the damage would have been far lower.

Plus the Designer assumes that they’ll collapse into Operator mode during certain periods in the future. By implementing automated pruning of even their own bad policies, the Designer stops the Operator version of themselves from refusing to dismantle their own bad policies.

A Note on Ethics and Power

Designing systems where the path of least resistance leads to desirable outcomes can sound, at first glance, manipulative or dystopian. This concern is legitimate—and Designers must address it directly.

This approach doesn’t remove agency—it reduces friction to achieve agreed-upon goals. People remain free to resist, exit, dissent, or subvert poorly designed systems. No amount of incentive design can prevent rebellion against genuinely harmful leadership.

In a well-designed system, dissent is not a bug to be suppressed, but a feedback mechanism to be integrated. Dissent means the system should be reformed.

In practice, the alternative to thoughtful system design is not freedom, but chaos. For workers, living inside a brittle, failing system with leaders in crisis management mode is far more exhausting and coercive than operating within a well-designed one.

Crucially, ethical system design must apply to leaders as well. Robust systems include mechanisms that surface dysfunction, constrain accumulation of bad policies, and allow the organization to correct leadership errors—including those introduced by the Designers themselves. A system that cannot challenge its Designer is already unsafe.

Revealing My Magic Trick

At this point you might assume that I’m a seasoned manager or executive.

I’m not a manager. I have zero management experience.

I merely happened to find a highly effective prompting strategy, which I share in Appendix A.

Most of the text in this essay was generated by applying that prompting strategy to publicly available free AIs (and me rewriting generated ideas into cleaner forms).

So this entire essay is a proof-of-concept that this prompting strategy works.

You too can use that prompting strategy to ask AI how to design Superconductive Systems. And if you do and implement those, your job as a manager gets a lot easier and less tiring.

After all, this prompting strategy let someone with zero management experience produce suggestions that feel useful even to seasoned managers and executives.

Hence, if people with actual management experience use this prompting strategy, they will be able to design highly effective and resilient systems indeed. Systems that even work when they’re not in the room, or when they have an awful month. Systems that work even if they don’t expend that much effort to keep it running, so that they can spend more time on strategy.

The only requirement is that you remain humble and build self-correcting systems (as described in Appendix B). Otherwise you build a highly effective system that doesn’t survive a period where you collapse into the Operator – and you will.

Conclusion

When the right thing really is the easiest thing, the system becomes superconductive—and everyone wins more with far less friction.

People will disappoint you. The question is: what systems will you build so that neither your flaws nor others’ determine the outcome?

Appendix A: Using AI as a System Designer, Not a Motivational Speaker

Most prompts make the AI try to understand humans, which AI does poorly.

By prompting the AI in a way that is completely congruous with this framework, the user allows the AI to leverage its incredible ability to optimize systems. This produces much more effective answers.

The Core Shift

Do not ask the AI:

“How do I get people to do the right thing?”

Ask instead:

“How must the system change so the right thing becomes the easiest, safest, and least costly choice?”

Designer Prompt Pattern

You must be blunt and realistic, otherwise AI will respond like a Naive Optimist.

1. Describe the actual state of the system.

Example: My team is operating in survival mode due to layoffs and deadline pressure. The todo list is so long that it demotivates people.

2. Describe the actual behavior of people.

Example: Developers are stressed, overloaded, and optimizing for plausible deniability, short-term hacks and minimal effort. Sales people overpromise new features.

3. State which solutions will fail.

Example: People cannot reliably process long-term tradeoffs. Any solution requiring motivation, alignment, trust-building, extra meetings, or moral appeals will fail. Excessive monitoring or public shaming will fail because it demotivates people.

4. Ask to design the system so the desired outcome becomes the path of least resistance by adjusting incentives, defaults, workflows, or information flow.

Example: Design the system so effective development becomes the path of least resistance by adjusting incentives, defaults, workflows, or information flow.

Iterate ruthlessly: If the AI proposes categories of solutions that won’t work in practice, run the prompt again with those solutions added to step 3. Repeat until the proposals survive real-world stress-testing.

Full Example Prompt

My team is operating in survival mode due to layoffs and deadline pressure. The todo list is so long that it demotivates people.

Developers are stressed, overloaded, and optimizing for plausible deniability, short-term hacks and minimal effort. Sales people overpromise new features.

People cannot reliably process long-term tradeoffs. Any solution requiring motivation, alignment, trust-building, extra meetings, or moral appeals will fail. Excessive monitoring or public shaming will fail because it demotivates people.

Design the system so effective development becomes the path of least resistance by adjusting incentives, defaults, workflows, or information flow.

Another Full Example Prompt

Household tasks aren’t being completed. One spouse is the manager and gets overburdened by managing tasks. The other spouse is a passive follower. Telling the other spouse to be more proactive doesn’t work. Design the system so effective execution of household tasks becomes the path of least resistance by adjusting incentives, defaults, workflows, or information flow.

Try using a prompt of this kind to ask AI for help with a problem you’re currently dealing with. You may be able to get a genuinely helpful idea within minutes.

Appendix B: Building Resilience By Watching The Watcher

The Designer does not trust their own policies. The Designer assumes blind spots, unseen second-order effects and emotional or ideological attachment to bad policies – including in themselves.

The Designer designs systems that remove the Designer’s own policies if they are wrong.

One example of this is the Devil’s Advocate Loop, which automatically uncovers and prunes bad policies:

Every six months, commission a devil’s advocate team with full data access. Their job: criticize, break, and disprove any policy.

If people want to keep a policy that the Devil’s advocate team suggests pruning, then that defense must happen in public.

If a policy cannot be convincingly defended, the default is deletion.

One of those team members is an AI. This AI has zero authority or control: the only thing it can do is point to policies it thinks are bad, and then humans make the decisions.

Let devil’s advocate teams have different backgrounds each cycle. You can never have a ‘perfect’ devil’s advocate team, but rotating teams uncover different blind spots over time.

Or as another example: every new “bank” the Designer adds to the river should have an expiration date. At that date, the bank is removed unless it can be shown that it’s still beneficial. And the reasoning / defense must happen in public.

Or as another example: every “bank” the Designer adds must come with a documented condition under which the bank should be removed. If possible that removal should happen automatically. If that’s not possible, someone who is not the Designer looks at that every quarter.

That said, in all cases Chesterton’s fence should be kept in mind: you should be careful about removing fences or policies until the rationale behind the original establishment is understood. So when deciding whether or not to prune bad policies, investigate the historical reason why that policy was implemented.

If you’re inside a system and you’re unable to persuade people to change a bad policy, then a Designer move is to implement the devil’s advocate loop, and let gravity do its work.

Appendix C: When You Cannot Change A Toxic System

Sometimes you cannot change the river banks because they are fixed by law, rigid compliance rules, or chaotic leadership. Most people choose submission (letting the chaos crush them) or rebellion (fighting a war they can’t win).

If the system is incredibly toxic, sometimes the best move is just to exit.

Still, a Designer move is to act as a Step-Down Transformer—what a skilled Product Owner or middle manager often does in practice.

If the system above you is high-friction, toxic, or chaotic, you do not pass that energy directly down to your team. Instead, you create an Air Gap: you absorb the chaos and convert it into clear, manageable output.

A good Product Owner or middle manager buffers the team from upstream dysfunction, translates messy priorities into actionable work, and creates a “pocket of reality” where productive work can actually happen. You are the transformer between chaos and execution.

1. The Input (The Raw Chaos)

The world above you provides the fuel. Often, it is dirty fuel: panicked 10 PM emails, vague requirements, regulatory theater, or emotional outbursts.

2. The Processing (The Air Gap)

Instead of reacting, you translate. You absorb the noise so it doesn’t hit the people or the project.

The Translation Move: If a boss gives a vague, angry demand, you don’t pass the anger down. You strip the emotion away and hand your team a clear, calm requirement.

The Automation Move: If a compliance law requires a tedious 20-page report, you don’t complain about it. You design a simple template or a “once-and-done” checklist that makes the task a mindless 2-minute default for your team.

3. The Output (The Pocket of Reality)

By acting as a buffer, you create a Pocket of Reality—a small environment where things actually work, even if the surrounding organization is on fire.

The goal isn’t to ‘fix’ toxic executives or bad laws—it’s to make them irrelevant to your daily work.

This is also what good caregivers, parents and partners have traditionally done: buffering their family from stress, translating messy or overwhelming situations into manageable guidance, and creating a pocket of stability where people can thrive.

The principle is the same—you build a shelter that channels the downpour into a thriving garden.

Ironically, when someone or some system buffers people too effectively, the protected may start to believe the outside world isn’t dangerous at all. In doing so, the buffer itself can begin to look tyrannical, or people inside the system may turn into Naive Optimists.

For this reason, good buffers occasionally and deliberately expose context, not chaos: a calibrated view of the unbuffered outside world that preserves psychological safety while restoring accurate beliefs.

Likewise, whether you are a worker or executive, you should very occasionally verify that your middle-manager buffer is translating reality rather than concealing it—by checking raw inputs, constraints, or failure signals directly.

To the fullest extent permitted by law, the author has waived all copyright and related or neighboring rights to this work worldwide under the Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication.

No Rights Reserved.

In plain English, you can:

Steal it: Use the ideas, the text, or the structure.

Profit from it: Sell it, adapt it, build services around it, or use it commercially in any way.

Publish it: Including in commercial or non-commercial professional journals, either the original text or an edited version, without attribution.

Ignore the author: You don’t have to credit me, link back, or ask for permission. Seriously—don’t ask. Just use it. The world needs the ideas more than I need the emails.

This system is designed to be a “bank” for your own river.

If you found value in these banks and wish to support the building of future frameworks, you can Buy me a coffee. That said, I don’t know if or when I’ll next have a good idea.

Otherwise, go forth and build. The river doesn’t care who moved the rocks.